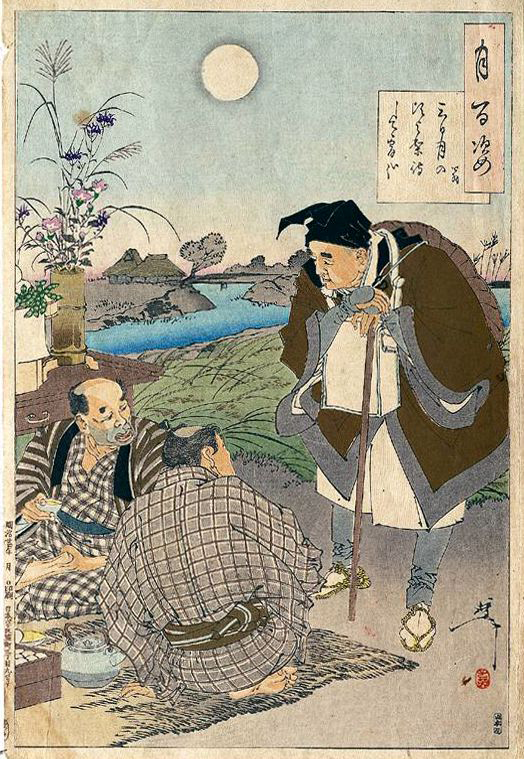

I’ve long been fascinated by the way that haiku focusses attention on a few words formally deployed in a confined space, yet at the same time opens the imagination to deeper and wider perspectives. But recently, during a prolonged period when full-time care for my late wife made it increasingly difficult for me to sustain the kind of extended concentration needed to compose a work of fiction, haiku took on a renewed value for me. It provided a mode of meditation through which I could re-centre myself while also keeping my imagination attuned to the living quick of language.

The tradition of classic haiku as practised in Japan by such masters as Matsuo Basho, insisted on a specific poetic structure of three lines consisting of seventeen syllables, with five placed in the first line, seven in the second, and five again in the third. The form was perfectly adapted not only to the syllabic and syntactical structure of the Japanese language, but also to that refined aspect of Japanese sensibility which responds to the natural world with exquisitely focussed attention to detail while remaining alert to the whole of which that detail is a part. In haiku, observed detail and the larger context are each apprehended as seamlessly implicit in the other.

Because the English language and the dominant tendencies of western modes of perception are of a different order, many English and American practitioners of haiku have adopted a more flexible and exploratory approach to both the traditional themes and the formal structure of the genre, often with deeply satisfying results. However, given the scattered state of my mind at the time when I resumed my interest in haiku, I felt that the particular discipline required by the classic seventeen syllable form might help me to regain a sharper degree of focus. Undertaking large pieces of written work still lay beyond my range, but seventeen syllables choreographed across three lines in a sentence or two… well, that felt like a feasible possibility.

As far as theme was concerned, I simply wanted to try to capture and define moments of sensory experience or of sudden insight which stirred a resonance in my imagination. Gradually, as I became aware of the challenges and opportunities it presented, the haiku form, with its apparent capacity to arrest the flow of time while simultaneously mirroring the inescapable transience of life, helped me to bring such moments through into clearer solution. Here are a few examples…

Mindful in absence,

haiku quickens memory

of how presence feels.

Haiku is the shape

of breath: life’s quickness briefly

caught, and then exhaled.

To live truthfully

among the contradictions.

Even trees tremble.

The heart as voice-box.

Listen: the blackbird’s body

throbs inside its song.

The creative life:

an unlonely aloneness

open to the world.

What has once been said

cannot ever be unsaid.

Words have bent the light.

To deny the soul

is to dissect a songbird

then not find a song.

High summer sunlight:

the mountain lake blinks open

its ice-lidded eye.

Paradox of love:

also to be at peace with

one’s own solitude.

Clouds in sunlight; then

night’s spectacle of stars: these

should astonish us.