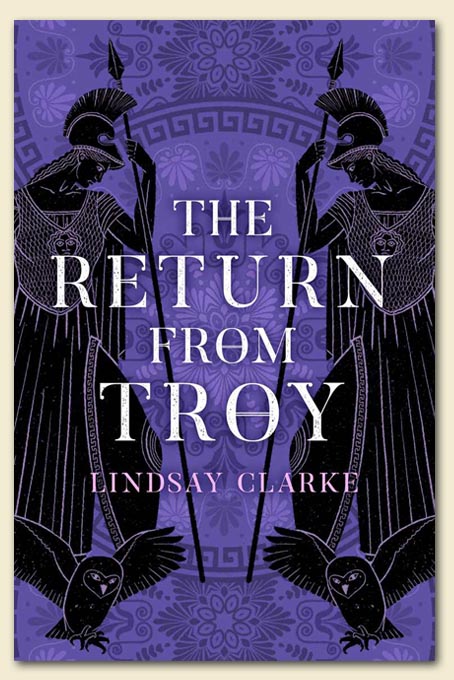

This month has seen the republication by HarperCollins of my two Troy novels in slightly revised form as The Troy Quartet in four paperbacks titled, A Prince of Troy, The War at Troy, The Spoils of Troy, and The Return from Troy. Reading them for the first time a young agent at United Agents wrote this: ‘I’m enjoying your work so much! I’d always wanted to get my head around the stories of Troy but had never known how before. Your books are a really accessible yet still satisfying complete retelling. I’m hooked.’

His response has encouraged my belief that these novels could engage the imagination of a new generation of readership, particularly, those who, like him, were gripped by Game of Thrones. To emphasise why I think that such a development might matter here’s an excerpt from an essay in Green Man Dreaming titled: The Mythic Imagination: from Troy to the Present Day:

If the stories of the Trojan War have inspired generations of great artists since Homer first sang them almost 3000 years ago, and still resonate in our own violent times, isn’t it because the human truths they celebrate – their accounts of passion and ambition, of daring and triumph, of loss and grief – are constant matters of the human heart? I began to write my own retelling of the stories in The War at Troy just as the war in Iraq was gathering force, and that conflict gave my work a sudden contemporary relevance. I watched the ‘shock and awe’ attack on Baghdad as I was thinking about the fall of Troy and was appalled at how little we seem to have learned over the last 3000 years. For as I saw it, the ancient stories understood that war is never inevitable unless we choose to make it so, and that the stated causes of a war may not be the real reasons why it is fought. One version of Helen’s story, for example, declared that she was never in Troy at all, only a phantasm of her which was so powerful in the minds of men that the Greeks believed she was there. This was also the case, you may remember, with the much-vaunted weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

Those old stories also seemed to understand that it is much easier to get into a war than it is to get out of it and that, no matter how much courage it may evoke, warfare eventually harms and corrupts everyone involved in it. So my novel The War at Troy begins with the quarrel among the goddesses over the golden apple, and the Judgement of Paris on Mount Ida, but it quickly gets caught up in the hot broil of human passion as Paris betrays his friend Menelaus for love of his wife Helen. From there it descends inexorably into the hideous carnage of war and its consequences. But it also felt important to honour the Greeks’ understanding that the gods have a part to play in warfare, and my solution was to honour them as archetypal powers which are always present within us and between us from one generation to the next.

Christianity has taught us to use the word God as the subject in such sentences as ‘God is Love’, but the Greeks would use the word ‘theos’ with predicative force, saying by contrast, ‘Love is a god’ or ‘War is a god.’ Such archetypal energies were invested with divine status by the Greeks because they are immortal. We mortals die; those impersonal powers never die. They engage each generation in those passionate conflicts which constitute what James Joyce called ‘the grave and constant’ matter of the human heart. Nor can we avoid them except at a cost to our own vitality; so it seems wiser to bring them into consciousness and try to relate to their power creatively rather than allowing our lives to be driven unconsciously along by them without our understanding what is happening and why.

This seems to me to be the real force behind the myths of the Trojan War.